CPTED for Marzahn, Berlin

The case of social, spatial and managerial renewal of a high-rise neighbourhood

Tobias Woldendorp summarizes for Safe Places/Favas.net a survey and assessment of the high-rise neighbourhood Marzahn in the city of Berlin (Germany). He conducted this analysis in collaboration with his then colleague Nicole Smits. This summary focuses on the application of the CPTED methodology: crime prevention through environmental design (more on CPTED in the Backgrounds section).

In 2006 and 2007 the neighbourhood Marzahn, located in former East Berlin, served as an ‘on site’ case study for a team of scientists and designers from both former eastern and western countries who worked within the ‘Crime Prevention Carousel’ partnership (see Acknowledgements). They visited high-rise housing in Marzahn, discussed possible solutions and noticed measures taken.

The first of the viewed measures were the topped-down apartment blocks of housing corporation WBG Marzahn. The topping-down work profited from the fact that the pre-cast concrete slab from the former DDR Plattenbau construction allowed to unplug bits of the buildings relatively easily. Even money could be generated from the demolition, since several stocks from the Plattenbau could be shipped to St. Petersburg to get a second life.

As a consequence, a mix of low-rise and high-rise houses disperses the solid building structure, creating a more varied, lively and verdant environment. The remaining stocks were coloured and turned from greyish into ‘Mediterranean’ colours. Additionally, the remodelling of the neighbourhood was completed with measures to promote art, thus achieving more diversity and a colourful environment, creating more variety and identifiable quarters.

Moreover, the public space was converted by means of a new, adapted profile. This measure made sense, since the topping down, hence, the creation of lower blocks implied new and more space to add for playgrounds and picnic meadows, as well as improved sunlight conditions (i.e. less shadow). In this regard the viewing teams noticed several additional measures of the housing corporation, such as the redesign of the old greyish paved front area into beautiful gardens with shrubs and herbs that could easily maintained by the tenants.

The latter observation ensured that it could be recognized that tenants and users will have more respect for their environment due to the accomplished high quality of housing and public space. This rule of thumb that links improved built environment with improved behaviour (e.g. respectful attitude), backs the conclusion that high quality refurbishment, landscaping and maintenance will save money in the long run as places are less likely to spiral into decline.

Instead of a surveillance by means of security cameras (CCTV) the viewing team was pleased to encounter a human concierge (in this case a friendly lady) who took care of all the issues in the block while overviewing the block-corridors. In this way management was taken care of 24 hours per day, from fixing lamp bulb, cleaning up and handle deliverances of parcels.

Marzahn was at that time aware on preventing residents with a higher social and economic status from leaving the area. In order to strengthen communal bonds, to enhance social engagement and to prevent crime. On top of that Marzahn installed several social measures, such as anti-aggression training for children and vulnerable youngsters, limited programs to aid people seeking jobs and an anti-graffiti program, combating graffiti by offering special areas were young people are invited to paint and spray freely. And last but not least: the communication between city and neighbourhood was properly managed, hence, the residents well-informed (e.g. about changes) and still involved in the long run.

Conclusion: in particular the well-balanced proportion of situational and social measures could set a good example for similar projects. On the structural level it is the embedding of the area into a diverse set of functions (leisure, work) and the co-existence of different constructional designs (high-rise, low-rise) that certainly looks promising for post-war housing precincts in Berlin and other cities in Europe.

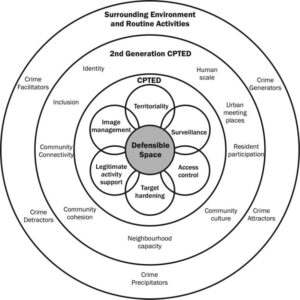

CPTED, second generation dynamic integrated model (Source: Paul Cozens, 2015; adapted from Cozens, 2014)

Acknowledgements

This project-summary is published under the responsibility of Tobias Woldendorp – https://www.woldendorpwildervank.nl/. It is based on the original report ‘Lessons learned: what we can learn from each other’ by Tobias Woldendorp and Nicole Smits – published as Chapter 5 in: Tim Lukas (ed.), Crime Prevention in High-Rise Housing. Lessons from the Crime Prevention Carousel. Duncker & Humblot ! Berlin, 2007.

Tobias Woldendorp and Nicole Smits (DSP-groep at that time) represented the Dutch equip of the ‘Crime Prevention Carousel’, a co-operation of five cities: Amsterdam, Berlin, Bristol, Budapest and Krakow. The Carousel-partnership was set up to investigate the problems of post-war urban building in Europe. The work was conducted under the co-ordination of the Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law (Freiburg/Germany) with funding from the AGIS programme of the European Commission.

Special thanks to DSP-Groep https://www.dsp-groep.eu/ (Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Image of concierge lobby by Nicole Smits (Berlin, September 2006). All other images by Rob van der Bijl (Favas.net, Berlin, October 2016), during additional site visits in Marzahn Nordwest.

The CPTED model (see figure) is taken from Paul Cozens and Terence Love, ‘A Review and Current Status of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED), Journal of Planning Literature 2015, Vol. 30 (4) 393-412.

This page is edited by Favas.net.

See also recent projects of Favas.net about similar subjects and projects like in Marzahn: Amsterdam-Zuidoost (Netherlands), Ghent (Belgium), Lodz-Widzew (Poland), Paris-Grigny (France).

Backgrounds

Definitely inspired by Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961) CPTED is invented by the American criminologist C. Ray Jeffery (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, 1971/1977) and the architect Oscar Newman (Defensible Space, 1972). According to the International CPTED Association (ICA) CPTED is a multi-disciplinary approach of crime prevention that uses urban and architectural design and the management of built and natural environments. CPTED strategies aim to reduce victimization, deter offender decisions that precede criminal acts, and build a sense of community among inhabitants so they can gain territorial control of areas, reduce crime, and minimize fear of crime. CPTED is pronounced ‘sep-ted’ and it is also known around the world as Designing Out Crime, defensible space, and other similar terms. – https://www.cpted.net/

The European chapter of the ICA, founded in 2001, is known as the European Designing Out Crime Association, E-DOCA. It is run by the Dutch Association for Safe/Secure Urban Design, Planning and Management/Maintenance (in Dutch: Stichting Veilig Ontwerp en Beheer, SVOB).

https://www.svob.nl/en/european-chapter/

https://www.svob.nl/

In Europe, CPTED was initially developed in Britain in the early 1990s by the UK Police Service and the Home Office with their concept of ‘Secured by Design’ – https://www.securedbydesign.com/. Inspired by this concept the Dutch police translated their crime prevention strategy regarding burglary into a handbook ‘Police Label Secure Housing’ (Politiekeurmerk Veilig Wonen, 1994) – https://www.politiekeurmerk.nl/. The Delft University of Technology has been a pathfinder in this regard by means of their comprehensive CPTED-based handbook and checklist (Van der Voordt and Van Wegen, 1990). In the years that followed, several CPTED-inspired manuals appeared in the Netherlands and other countries (e.g. Gerda R. Wekerle and Carolyn Whitzman, 1995; Tinus Kruger et al., 2001; Ita Luten et al., 2008).

![]()

Safe Places/Veiligwonen.nl developed their CPTED decision support system Predore – PREcedent DOcumentation & Registration (since 1993). The knowledge base of this tool stores a large collection of precedents reflecting safety problems regarding housing, public space, public transport facilities, schools, offices, shopping centres and all other features of our daily urban system – https://rvdb.favas.net/predore/. CPTED is summarized by Safe Places in just six criteria, labelled as visibility (1), accessibility (2), spatial zoning (3), attractiveness (4), offenders/criminals and victims (5), social and historical context (6).

Safe Places/Veiligwonen.nl cooperated with DSP-Groep / Woldendorp on a series of projects in the Netherlands (1999-2002), on safety assessments for urban planning and architecture, including projects regarding housing, public transport stations / hubs, and urban centres. They also contributed to the development of the Dutch Safety Impact Assessment tool (VER – Veiligheidseffectrapportage).

The Dutch concept of ‘veilig wonen’ can literally be translated as ‘safe living’. Finally, ‘Safe Places’ was chosen as the English name. This translation is based on research by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in South Africa. In the late 90s, we worked together here with Susan Liebermann and Tinus Kruger on crime prevention. The concept ‘safe places’ is derived from their manual (with Karina Landman) ‘Designing Safer Places’ (CSIR, Pretoria, South Africa, 2001). Beware, the term ‘safe places’ should not be confused with the fashionable phenomenon of ‘safe spaces’ that is common in many of today’s American universities.