Beemster Voices

Stories in an empowering landscape

Journalist Robert Niessen reports for Favas.net on daily life, work and culture in and around the Beemster, a historic Dutch polder and UNESCO World Heritage Site north of the Amsterdam metropolis in the Netherlands. His reports situate people in their living environment or during their work and other activities. Living in the Beemster, Robert closely follows the residents at their homes. He writes about his subjects (e.g. food) from the perspective of those who use their Beemster creatively and responsibly for agriculture, gardening, or other forms of goods creation and cultural capital. This approach provides a view of a landscape that is both context and raw material for empowerment. Robert delivers a bottom-up perspective on his world, devoted to important themes such as energy transition and climate adaptation by and for people.

Report 2

The modern way: dairy farmer Roos

Portrait of a modern farm with dairy cows, situated along the canal Beemsterringvaart. “The trick is: producing continuously at a fixed level”.

Sjaak Roos (1968) knows his 120 cows by number and recognises them from a long way of. The latter is important, because even when the herd is outside, he wants to be able to see which cow is in heat, so that she can be mated or inseminated quickly. The sooner the cow is pregnant again, the better, because it means that a calf will be born and that milk production will be reactivated. “Maintaining that rhythm of life is the most important thing to keep milk production at a steady level. And that is the art: producing at a steady level.” He therefore doesn’t measure the size of a farm by the number of head of cattle; “No, you have to look at how much product milk you produce.”

Jan Roos (1941), Sjaak’s father, still gave his cows names like Kee, Klara or Maartje. With 25 head of cattle that was still doable, just like manual or semi-automatic milking. But with the growing herd this soon became unfeasible and that is why there are now numbers in the meadow and milking is outsourced to milking robots. The cow itself has also been ‘scaled up’: from an average of four thousand litres of milk per year in 1960 to eight thousand litres today. The average dairy cow is ‘out of production’ around the age of five and sent to slaughter.

Forwarding system

The cattle business is constantly evolving, but some characteristics of the farm are unchanging. It is a family business, which means that the work is a constant interplay between the – usually three – generations. “Everyone works together”, is the unanimous response in the discussions at the coffee table. You do everything together and if necessary, family members help out, with the haying, for example. You also share your joys and sorrows with each other. Another characteristic is that the farm is usually passed on from generation to generation. Sjaak: “It is a transmission system: you take over the farm with all its joys and burdens. Think of the real estate, the land, the livestock, but also the debts that you have to try to push away, until it is the turn of the last owner and has to settle for several generations. It doesn’t matter how you pay off those debts, such as the mortgage and the deferred tax claim. As long as you keep the business financially healthy and you also keep investing.”

Not sure yet

The farming branch in the Roos family goes back many generations, but the ownership of a farm is due to Jan’s grandfather who bought the farm from his father-in-law at the time. In 1970 Jan took over the farm from his father and since 2006 the ‘joys and pleasures’ are in Sjaak’s name. Not that Jan is retired. No, he lives with his wife Diet right next to the farm – in Oudendijk, a village on the edge of the Beemster, and he works every day.

As the youngest of three children, Sjaak has naturally followed in his father’s footsteps. Whether one of his two sons or his little daughter will choose the same path later on, is hard to say. Sjaak nods to his eldest son and says: “When I was 16, I was also busy with other things”.

Farmers’ cooperative and cheese factory

To escape the 24-hour duty of the farm every now and then, father Jan makes long trips on his racing bike in the summer and in cold winters he goes for long skating tours on the ice – two favourite outdoor sports in the Netherlands.

Son Sjaak is especially active in village social life and he regularly goes out to the farmers’ cooperative to which he supplies milk: CONO Kaasmakers, founded in 1901 and located in the heart of the Beemster. Sjaak is particularly committed to sustainability projects; here too, times have changed.

Report 1

Portrait of a small, traditional farm and artisan cheese factory

The traditional way: the story of cheesemakers Jan and Ruth

Jan and Ruth Verdegaal became farmers thanks to great-grandfather Gerrit Verdegaal. The family has been associated with livestock farming for generations, but great-grandfather farmed so well that he left a farm to his three sons (the daughters each inherited a milk churn). Also the making of cheese had been in the family for a long time. Thus Jan (1958) and Ruth (1963) grew up milking Blaarkoppen (a breed of cows), churning butter and making cheese. In 1969, the family moved from Lisse to Oudendijk, a village on the edge of the Beemster. Of the six children, only Jan and Ruth felt at home on the farm. That they went to the agricultural college in Hoorn was therefore a matter of course. And when their father died in 1998, they just as naturally followed in his footsteps.

“There is always a metre of grass growing in a year”

Since then, the brothers have increased the number of cattle from thirty-five to sixty Blaar heads. They have added another barn and expanded the land from seventeen to thirty-five hectares. Machines have been replaced, the bookkeeping has become more complex and their mother, Toos, has gradually withdrawn from the household. Apart from that, it is as if time has stood still here. Just like in the old days, the animals and the seasons determine the rhythm in and around the farm. Year in and year out. “It’s always the same,” says Jan, “and yet always different” – also because of the wonderful change of seasons. But no matter how the seasons turn out, in the end it makes no difference, because – as Ruth soberly observes – “There is always a metre of grass growing in a year”.

The eternal repetition also has its advantages. Jan: “You can try again every year. If something is not going well now or you think it could be done better, then next year you get the chance to do it slightly differently.” Only the ringing of the shop bell breaks the rhythm of the farm. Customers come from far and wide to buy what is, according to the newspapers, ‘the best butter in the Netherlands’. Or naturally matured cheese, or buttermilk. Recently, they also started selling their ‘own’ meat, but they are not entirely happy with that yet. Nevertheless, cattle breeding in the Beemster started at the beginning of the 17th century: fattening cattle to sell meat to consumers all over Europe.

Background

The Beemster introduced

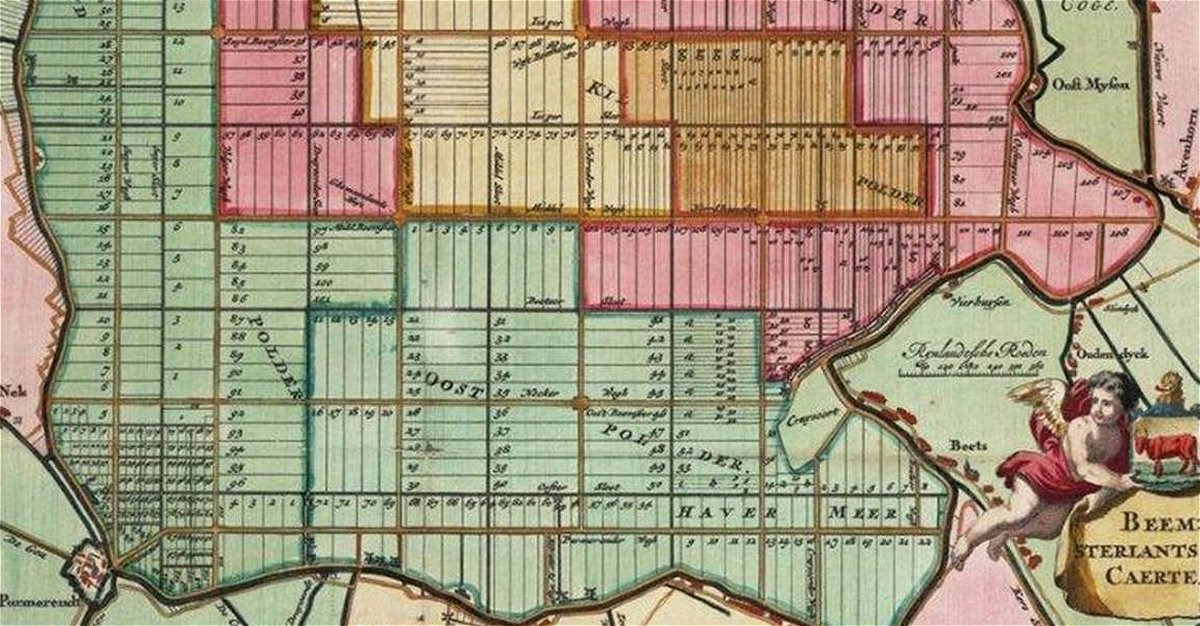

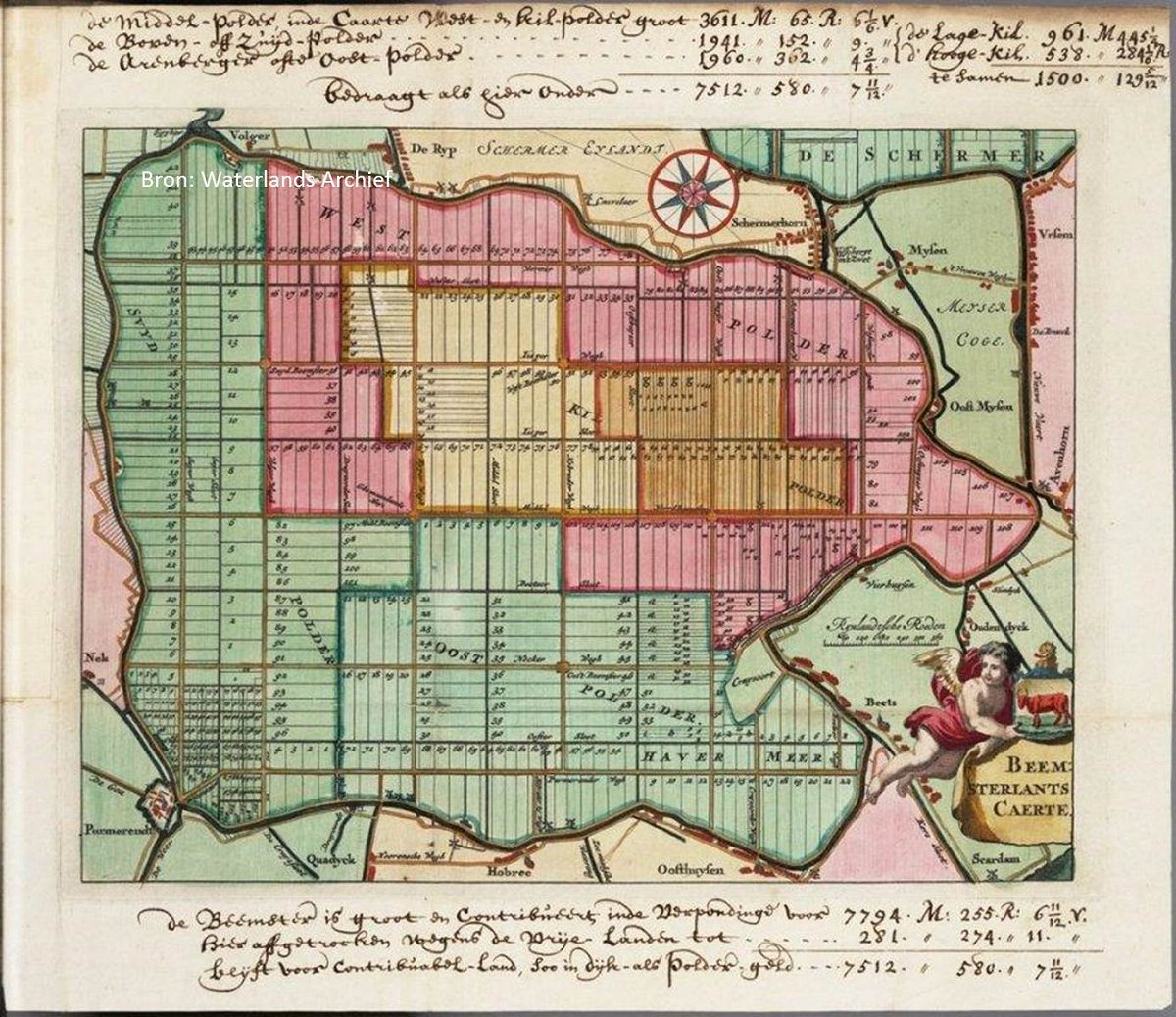

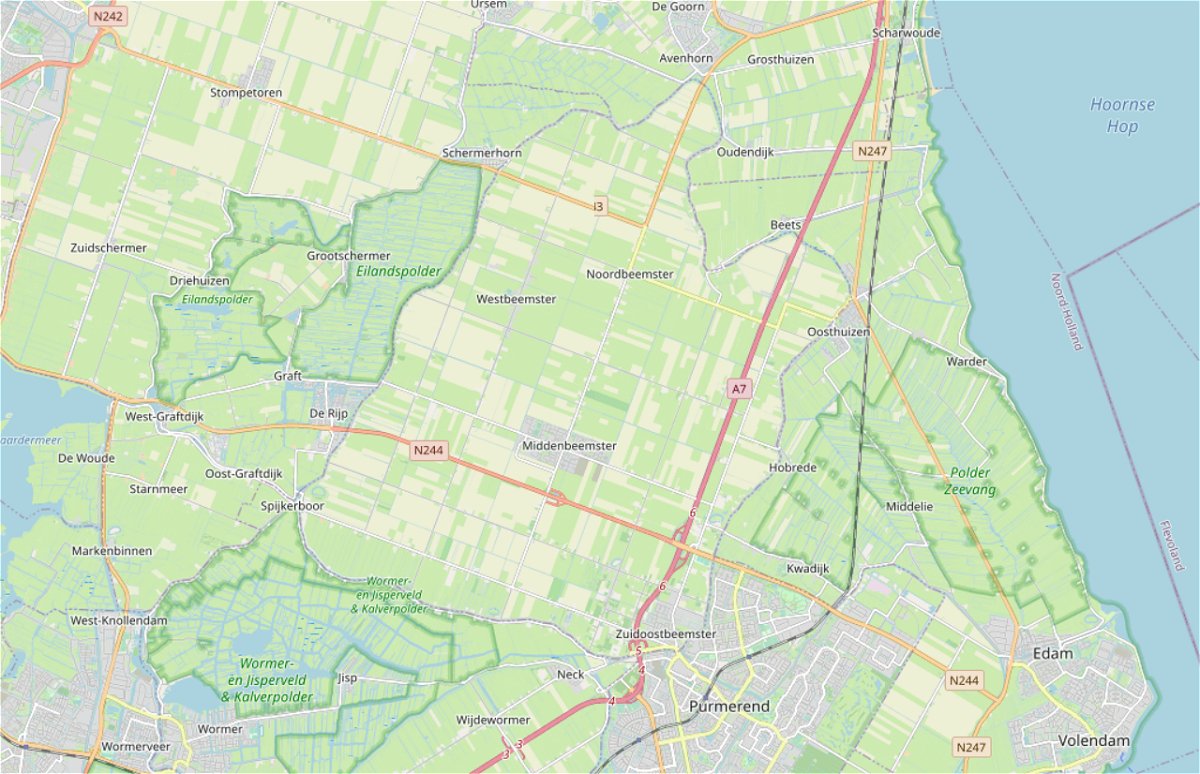

Droogmakerij the Beemster (Beemster Polder) was constructed in 1612 as one of the first initiatives in Holland in reclaiming agricultural land from a body of water. The new land has been obtained by pumping water out of the former Beemster Lake, using 43 windmills. The area covers 72 km² and lies on average 3.5 meters below sea level. The new land was used for farming and a lot of wealthy people from the city of Amsterdam built their second home here. These lavish houses and characteristic wind mills have long since almost all disappeared, but the rational geometric pattern of the roads, dykes, canals and land – developed in accordance with the principles of classical and Renaissance planning -, remained. ‘This mathematical land division was based’, as the Unesco describes, ‘on a system of squares forming a rectangle with the ideal dimensional ratio of 2:3. A series of oblong lots, measuring 180 metres by 900 metres, form the basic dimensions of the allotments. Because of this ingenious master plan, Unesco (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) designated the Beemster a World Heritage Site in 1999.

Credits

All images and texts by Robert Niessen.

Except:

Historic Beemster map (courtesey Waterlands Archief)

Today’s Beemster map (courtesey OpenStreetMap)

Webpage editors: Robert Niessen & Favas.net

See also:

UNESCO heritage list: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/899/

VISIT Beemster (in Dutch only): https://visitbeemster.nl/

beemstervoices.nl/ (in Dutch only)

robertniessen.nl/ (in Dutch only)

Map: Beemster and vicinities today