Combating transport poverty with the bus

Favas.net is intensively involved with mobility, or rather, with the issue of insufficient and unfair mobility. Because mobility is a crucial prerequisite for people to be able to maintain themselves in society. No one gets far without mobility. Therefore, there is a serious risk of so-called transport poverty if people lack access to sufficient and suitable means of transport or if they cannot use these means effectively. Read more about Favas.net’s transport poverty research.

Transport poverty is a multifaceted problem (Van der Bijl, 2020). Nevertheless, it is possible to work on solutions. Firstly, by combating poverty in general. And secondly, by making better and greater use of bicycles and combating forced car dependency as much as possible, which, incidentally, is not easy. Therefore, public transport is perhaps the most important means of combating transport poverty and the unfair distribution of mobility resources. It is well known that establishing and operating public transport is certainly not easy. Recent research and accompanying book publication (Van der Bijl & Van Oort, 2024) set out the possibilities that the bus offers to successfully combat transport poverty.

Nantes – Combating transport poverty with the bus.

Over the past two decades, the phenomenon of transport poverty has emerged, particularly in England; see, for example, the report by the charity Sustrans (2012). This form of poverty leads to social exclusion, as extensively researched by Lukas (2004 & 2012) and Currie (2011). Available and sustainable mobility are a prerequisite for inclusivity, while public transport, such as buses, represents a crucial implementation of this prerequisite. If this prerequisite is not or insufficiently met, social injustice arises. The term ‘equity’ refers to fairness and justice and the need to identify and prevent ‘involuntary transport disadvantages’ (Jeekel, 2018) that can lead to serious transport poverty. Researchers such as Banister (‘Inequality in Transport’, 2018) and Martens (‘Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems’, 2017) have firmly placed this topic on the agenda of research and policy. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are in line with this, in particular SDG 11.2 entitled ‘Access for all; expansion of public transport’ (UITP, 2023).

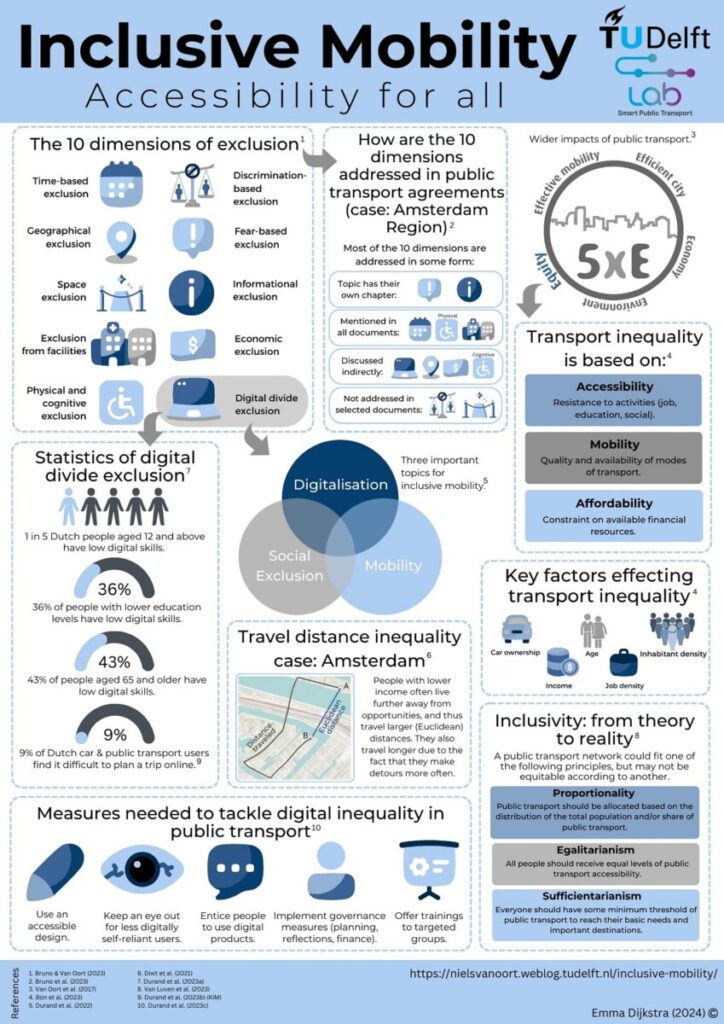

Poster Inclusive Mobility (Emma Dijkstra (2024): ‘equity’ explained and summarized in all its facets for mobility.

Inclusive mobility can be summarized by the motto ‘accessibility for all’, in which ten dimensions of possible exclusion can be explored from the literature (Luz & Portugal, 2021; Bruno & Van Oort, 2023) – see also the poster above by Emma Dijkstra. This motto offers a starting point for the application of the bus. More than the heavy, usually rail-based forms of public transport, the ‘regular’ bus (conventional, modal, or small) is suitable for pragmatically achieving sufficient accessibility close to the origin and destination. On an urban scale, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) or otherwise upgraded buses can be used to handle larger flows in all those situations where rail-based public transport is lacking (for whatever reason). Moreover, with the bus, it is easier than with rail-based public transport to allow bus lines to branch out on heavy corridors near the ends of the line(s). In short, the bus in its various forms is relevant for combating transport poverty and achieving equitable mobility.

Bogotá feeder busus – shuttles linked to BRT

The complex equity issue of accessibility inequality and transport poverty, particularly in the case of BRT, appears to be a topic primarily within the Global South. According to Wirasinghe et al. (2013), some findings in the literature support the assumption that BRT systems would promote equitable mobility here. For example, a reduction in average travel times was observed in Bogotá just a few years after the system opened, which would provide mobility benefits specifically for the less privileged residents of the metropolitan area. Other studies, for example, quantified improved accessibility options within the then-existing BRT corridor in New Delhi.

Wirasinghe et al. (2013), on the other hand, also note that research does not support the occurrence of accessibility benefits for disadvantaged travellers. It is not the very poorest, but middle-income groups that benefit from BRT. Venter et al. (2017) draw a similar conclusion. According to these authors, research on BRT in Africa, Asia, and Latin America often suggests that BRT offers significant benefits to low-income groups. Travel time and cost savings are cited, as well as improved access and benefits related to safety and health. However, Venter et al. argue that these benefits primarily accrue to middle-income users, because the spatial and functional scope of BRT and the relatively high fare significantly hinder the accessibility of bus services for the poor. They conclude that BRT can only be truly socially sustainable if it is linked to additional transport that offers local accessibility and is aligned with how and where the poorer population is housed. Nevertheless, small buses in Bogotá connect poorer neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the metropolis and offer connections at BRT stations. In this way, the bus system combats transport poverty and transport injustice as much as possible. It also partially addresses the problems identified by Wirasinghe et al. and Venter et al.

Metz is a good example in Europe of a BHLS (Bus with High Level of Service).

Under the condition mentioned by Venter et al., BHLS (Bus with High Level of Service) and all other forms of improved bus transport can also play a role in the equity challenge in Europe. For example, bus projects in French and Spanish cities are often justified not only on the grounds of efficiency but also by the understanding and associated policies that accessibility and public transport connections are essential for a liveable and healthy city. Buses are used there to make and keep the city accessible for its residents and businesses. The high-quality bus system in Metz, France, is a striking example. In some other places in Europe, such as the Netherlands, this role has become less evident in recent years. While the bus’s connecting function is generally improving, its accessibility function is eroding.

The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency has carried out ‘accessibility analyses’ (Bastiaanssen & Breedijk, 2022). Researcher Bastiaanssen is quoted in an article from OV-Magazine (March 2, 2023) about transport poverty in combination with the scaling down of some timetables and the disappearance of bus stops. “Buses are often used to quickly get to a train station or city centre, but this sometimes eliminates winding routes through neighbourhoods and villages. Residents in these areas are therefore often forced to rely on a car to reach certain amenities. (…) We have the right to education and healthcare, but we don’t have the right to get to school or the hospital within a certain timeframe. That’s actually strange.” The solution seems simple here: bring back the missing bus and improve the one that’s still there.

Conclusion

The bus can combat transport poverty. Moreover, it can promote more equitable mobility. Public transport, such as the bus, is a basic social amenity, just like urban sewerage and public lighting. There is no fundamental difference between improving the bus and providing a public library. “Such facilities exist for users. They fulfil a social function”, according to the final conclusion of Van der Bijl & Van Oort (2024). Or, in the words of Higashide (2019): “… each step to improve bus service represents a meaningful improvement in the lives of hundreds of people who wait at a particular bus stop, or the thousands who use a specific bus route, or the hundreds of thousands who ride the bus in a given city.”

Impressions

Combating transport poverty with the bus. The many forms of bus transport – conventional, enhanced, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), and so on – contribute to inclusive mobility and combating transport poverty in numerous places. To illustrate, here are some impressions of cities worldwide, listed alphabetically.

Almere (Netherlands) – The high-quality bus service in this ‘new town’ has grown alongside its expansion into a medium-sized, multi-centre city since its founding in 1976. Although car use is relatively high, many residents still rely on the bus.

Bogotá (Colombia) – Finally, rail-based public transport (a metro line and a regional light rail line) is being built in this metropolis, but for now, everyone is dependent on the BRT system (Transmilenio). Without this bus, Bogotá would have ceased to function long ago. Nevertheless, the congestion defies imagination.

Paris/Île-de-France – In the Paris metropolitan area, the 1500-line bus network is the de facto backbone of public transport. A crucial function of this network is to connect to the metro and train lines, or, where rail is unavailable, to provide services for heavier bus lines such as Trans-Val-de-Marne (TVM), which carry enormous passenger volumes. For that matter, the tram serves a similar function in Paris/Île-de-France.

Fukuoka (Japan) – For Japan’s sixth-largest city, Fukuoka has relatively little rail infrastructure. Therefore, buses play a key role in public transport, which is dominated by the operator Nishitetsu. Passengers appreciate this service, which connects virtually every part of the city. However, the buses are slow and often get stuck in traffic, due to the almost complete lack of dedicated infrastructure.

Istanbul (Turkey) – Although public transport services for this metropolis (metro, light rail) have been under development for decades, many travellers still rely on bus taxis (Dolmuş) and minibuses. Fortunately, a pragmatic decision was made to implement a complementary BRT system (Metrobus). Unfortunately, this bus is heavily overloaded, but that’s actually true for all public transport in Istanbul.

Los Angeles (California, US) – Besides rail-based public transport and regular buses, supplemented by BRT, LA still has three so-called ‘Metro Rapid’ bus services, including the 720 (Downtown – Santa Monica), which is essentially an accelerated version of the regular route 20 along the same route. In LA, poorer residents, in particular, are completely dependent on buses.

Seoul (South Korea) – The main lines are served by the blue buses (‘trunk buses’). The supplementary services of the green buses (‘branche buses’) serve as a connecting service. Not pictured: the red ‘rapid buses’ that serve the entire metropolis and the small, green ‘village buses’ that provide connections to metro stations and major stops on the main bus network. It goes without saying that, in addition to the metro, this four-unit bus system is of great importance to travellers in Seoul.

Taipei (Taiwan) – Besides the overcrowded metro, public transport in this metropolis also relies heavily on the equally busy and extensive bus network. Many buses use the dedicated bus lanes in the city centre, such as here in the median strip of Nanjing East Road. Shuttle bus R25 is on its way to Beimen metro station (photo right). Express bus 605 also uses the bus lane there (photo left).

More about the bus

See Favas.net for more news about the bus in Los Angeles, Paris-Grigny, and Jakarta.

Acknowledgements

Text, photos & editing: Favas.net – the text is partly an English translation of sections 3.6 and 6.9 of the Dutch book ‘Betere bus’ (Van der Bijl & Van Oort, 2024).

Research: Rob van der Bijl (Favas.net & Ghent University, Belgium) and Niels van Oort (Delft University of Technology, Netherlands).

Poster ‘Inclusive Mobility’: Emma Dijkstra (Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, 2024).

Selection of literature

= Banister, D. (2018). Inequality in Transport. Alexandrine Press.

= Bastiaanssen, J., Breedijk, M. (2022). Toegang voor iedereen? Een analyse van de (on)bereikbaar-heid van voorzieningen en banen in Nederland. Den Haag: Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving.

= Bruno, M., Van Oort, N. (2023). The ten dimensions of transport related social exclusion, position paper.

= Currie, G. (2011). New Perspectives and Methods in Transport and Social Exclusion Research. Emerald Publishing.

= Higashide, S. (2019). Better buses. Better cities. How to plan, run and win the fight for effective transit. Island Press.

= Jeekel, H. (2018). Inclusive Transport; Fighting Involuntary Transport Disadvantages. Elsevier.

= Lucas, K. (2012). Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now? Transport Policy, vol. 20, p.105-113.

= Lucas, K. (2004). Running on empty: Transport, social exclusion and environmental justice: Policy Press.

= Luz, G., Portugal, L. (2021). Understanding transport-related social exclusion through the lens of capabilities approach. Transport Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.2005183.

= Martens, K. (2017). Transport Justice: Designing Fair Transportation Systems. London, New York: Routledge.

= Sustrans (2012). Locked out: transport poverty in England. Bristol, Sustrans.

= UITP (2023). Why public transport is key to archive the SDGs. UITP, 24 November 2023.

= Venter, C., G. Jennings, D. Hidalgo, A.F. Valderrama Pineda (2017). The equity impacts of bus rapid transit: a review of the evidence and implications for sustainable transport. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. DOI: 10.1080/15568318.2017.1340528.

= Wirasinghe, S.C., L. Kattan, M. M. Rahman, J. Hubbell, R. Thilakaratne, S. Anowar (2013). Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) – a review. International Journal of Urban Sciences, March 2013 DOI: 10.1080/12265934.2013.777514.