Safety is no chewing gum

Speech by Rob van der Bijl (Veiligwonen.nl/SAFEPLACES) at the city of The Hague, Netherlands, April 17, 2003

The purpose of SAFE PLACES is to differentiate thinking about safety. My speech is about this problem. How can safety and urban planning be addressed and interlinked comprehensively without falling into simple dogmas or undifferentiated pretensions? Contrary to what slogans of many politicians suggest, safety isn’t a fixed feature of the city and its buildings. Safety isn’t a kind of chewing gum that sticks to walls.

Los Angeles, California, US

In the course of the nineties, my thinking about social safety in relation to the built environment has been changed due to a number of foreign experiences. Los Angeles represents such an experience, and certainly not the most unimportant one. LA shows clearly how safety in many cases is a matter for the well-off and rich people. LA is an extremely segregated city. Its public domain is increasingly being sacrificed to private interests. Those who can afford social safe and secure life, predominantly live in beautiful, uphill neighbourhoods, isolated from the rest of the city.

The publicist Mike Davis is darkly about the future of LA, see his book ‘City of Quartz’ from 1990. Fear determines the structure and form of this city. Safety thinking leads to an ‘Ecology of Fear’, according to the title of the book that Davis published in 1999. Maybe Davis is too gloomy, but his studies indeed give enough reason to differentiate thinking about safety. The ‘Golden Library’ in Hollywood by architect Frank Gehry is, as it were, turned inside out. The public character is only present within. From the outside it is a bunker, says Davis. Douglas Coupland has also written about LA, about Brentwood, a leafy neighbourhood somewhere behind the coast near Santa Monica. Most of Brentwood is located north of San Vicente Boulevard. But Coupland doesn’t not know the exact place. He doesn’t mind that either. He is searching, and much less resolute than Mike Davis.

Douglas Coupland has also written about LA, about Brentwood, a leafy neighbourhood somewhere behind the coast near Santa Monica. Most of Brentwood is located north of San Vicente Boulevard. But Coupland doesn’t not know the exact place. He doesn’t mind that either. He is searching, and much less resolute than Mike Davis.

Brentwood is known despite the unclear bounderies. Marilyn Monroe lived and died here. And here in the summer of 1994 O.J. Simpson (supposedly not) murdered his wife. Brentwood isn’t a ‘gated community’. But the observations of Coupland in his ‘Polaroids from the Dead’ (1996) prove that saftety for the elect can also be realized within the urban domain in a very subtle way.

Johannesburg, South Africa Another experience. The city of Johannesburg. Even more than LA ‘Jo’burg’ is the stage of an overwhelmingly derailed safety thinking. In recent years, apartheid planning has been de facto reinforced. On top of old contradictions new ones are stacked. Security of houses and (public) buildings got out of hand completely. Johannesburg is a city, ‘raw in your face’. Indeed, the urban reality is chocking. I wrote an article about that in the Dutch magazine ‘Blauwe Kamer’ (‘Raw in your face’).

Another experience. The city of Johannesburg. Even more than LA ‘Jo’burg’ is the stage of an overwhelmingly derailed safety thinking. In recent years, apartheid planning has been de facto reinforced. On top of old contradictions new ones are stacked. Security of houses and (public) buildings got out of hand completely. Johannesburg is a city, ‘raw in your face’. Indeed, the urban reality is chocking. I wrote an article about that in the Dutch magazine ‘Blauwe Kamer’ (‘Raw in your face’).

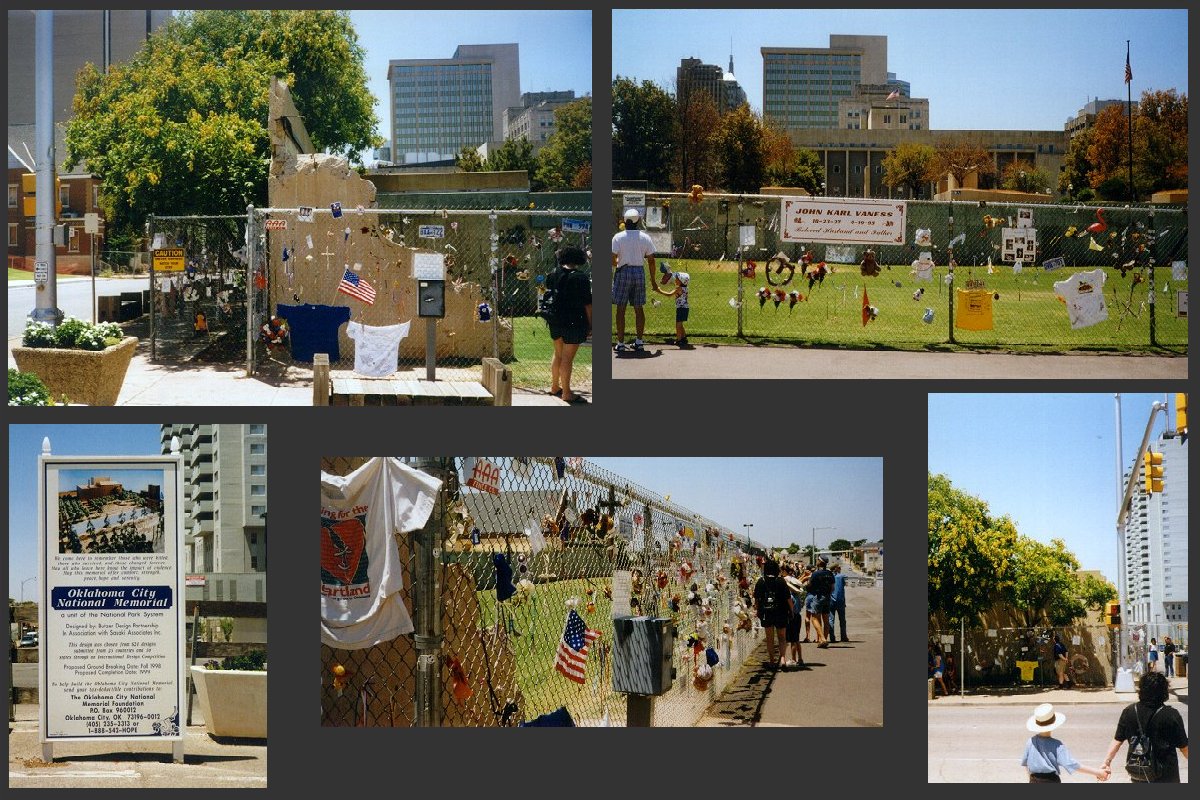

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, US In LA and Johannesburg you would wish that safety thinking was abandoned. But unfortunately many threats are very real. This is obviously the case in Oklahoma City where a building was blown up by a militaristic madman some years ago. The site is now a monument. In 1998 I made tourist pictures of the way in which the memory of the many dead was kept alive. Thinking about safety is inevitable. Oklahoma City doesn’t stand alone. Later attacks would again underline this.

In LA and Johannesburg you would wish that safety thinking was abandoned. But unfortunately many threats are very real. This is obviously the case in Oklahoma City where a building was blown up by a militaristic madman some years ago. The site is now a monument. In 1998 I made tourist pictures of the way in which the memory of the many dead was kept alive. Thinking about safety is inevitable. Oklahoma City doesn’t stand alone. Later attacks would again underline this.

Safety

Thinking about (social) safety and the built environment is dominated by two, partly overlapping disciplines. The first represents technical security. Besides a discipline, ‘security’ is primarily a ‘business’. The second is commonly referred to as CPTED (pronounced as ‘septet’): ‘Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design’; also referred to as ‘situational crime prevention’. Many checklists originate from this field. They are mostly based on insights from the ‘ecology of crime’, a kind of shoestring discipline, particularly well-developed in the US.

Security and CPTED are two sides of the same coin: No technocratic approach, yet instrumental

No technocratic approach, yet instrumental

Within the disciplines and related frames of Security and CPTED, safety is conceptualized as an almost intrinsic property of buildings and spaces. As if safety is a type of chewing gum that sticks to the walls and paving.

Non-technocratically, however, security is more of a relationship. At a given moment the built environment is performing in terms of safety. Hence, safety is performance inextricably linked to the way in which that environment is formed and used.

Safety is not a static property, but must be regarded as outcome of a dynamic equilibrium. Precise this view on safety allows an instrumental application of nuanced safety thinking.

Public space as an example Place des Terreaux, Lyon, France

Place des Terreaux, Lyon, France

Topic:

Spatial design

Condition:

Planning public space

Form:

Layout and design of public space, infrastructure & facilities

Use:

Staying, being and connecting

Performance:

Protection, ambiance, aesthetic and architectural quality

References

Rob van der Bijl (2006), Raw in your face. Johannesburg: oude en nieuwe tegenstellingen in Zuid-Afrikaanse stedebouw. In: Blauwe Kamer nr.6, 2000, pp.29-35.

R.V. Clarke (1992), Situational crime prevention. Successful case studies. New York.

Douglas Coupland (1996), Polaroids from the Dead. Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Jean-Piere Charbonneau (2000), Transformations des Villes, mode d’emploi. Paris.

Mike Davis (1990), City of Quartz. Vintage Books Edition (March 1992).

Mike Davis (1999), Ecology of Fear. Publisher: Henry Holt.

D.J.M. van der Voordt & H.B.R. van Wegen (1990), Sociaal Veilig Ontwerpen. OSPA/TU-Delft. Backgrounds

Backgrounds

This text is an adaptation (Favas.net, February 2019) of Rob van der Bijl’s lecture previously published by Veiligwonen.nl for the former ROZM workshop of the city of The Hague (April 17, 2003).

See also the masterclass ‘Ontwerpen met Veiligheid’ (‘Design with Safety’), Rob van der Bijl, Delft University of Technology, January 24, 2012.